Percolation Concepts in Hydrology

Contents

- 1 Percolation Concepts and the (Non?)-Intersection of its History With That of Hydrology

- 2 Institutional History of Hydrologic Sciences: AGU, NSF, CUAHSI, and Opportunities Delayed

- 3 Summary of Juxtaposed Histories

- 4 Percolation Advances in Hydrologic Science

- 5 Summary, Including Relevance to Hydrologic Sciences, Present and Future

- 6 Conclusion

- 7 References

Percolation Concepts and the (Non?)-Intersection of its History With That of Hydrology

Percolation theory's early use, in accord with its name, addressed problems of filtration of toxins through the use of masks (Broadbent and Hammersley, 1957). This specific application exploits percolation theory's description of the connectivity of pathways accessible to the contaminants present in the gas. The use of percolation concepts in hydrology, however, has been limited, a kind of conundrum, since this modern theory of statistical mechanics, a branch of the theory of complex systems, is known to be especially suited to deal with problems of connectivity in systems with heterogeneities (either correlated or uncorrelated) at multiple scale (Hunt and Sahimi, 2017). These are the oft-cited problems plaguing subsurface hydrology (e.g., NRC, 1996; Kitanidis, 2015). Hydrology's new alliance with soil physics emphasizes fluxes across the atmosphere/soil boundary, encountering complications deriving from the problems subsurface hydrology has with scale, connectivity, and heterogeneity, as they relate to flow and transport. As stated by Muhammad Sahimi in Reviews of Modern Physics in 1991, there is scarcely a problem relating to porous media, which does not have its roots in percolation theory, the theory of the scale-dependence of connectivity in such networks as the soil. From the scale dependence of connectivity, percolation then generates specific results for the scale dependence of flow and transport properties. When pore-scale (or any scale) variability of the local hydraulic conductivity is large (almost always), the hydraulic conductivity can be calculated using a percolation concept known as critical path analysis (CPA) (Pollak, 1972; Friedman and Seaton, 1998; Hunt, 2001; Hunt and Sahimi, 2017; Ghanbarian et al. 2016; Ghanbarian, 2020), in which the minimum fraction of smallest resistances to flow that form an interconnected path, is quantified using the critical fraction for percolation. In such cases, solute transport is still controlled by the dominant flow near the percolation threshold applied using CPA. Thus, e.g., solute transport results from percolation theory, often assumed relevant only near the threshold, apply almost universally (Sahimi, 2022).

Percolation Development for Porous Media Through the Chemical and Petroleum Engineering Disciplines

The major development of percolation theory in porous media was triggered in the late 1970's by a group of chemical engineers at the University of Minnesota, namely H. Ted Davis, Skip Scriven, and their proteges, including Muhammad Sahimi and Kishore Mohanty, whose work spanned chemical and petroleum engineering. The importance of the research was not lost among other practitioners in the oil industry, including work by Katz and Thompson at Exxon and Koplik, Wilkinson, and Willemson at Schlumberger Doll. Although this work blossomed in the 1980's, it scarcely penetrated the hydrologic sciences. Nevertheless, percolation theory, with its quantification of the impacts of heterogeneity on the scale-dependence of connectivity, provides a fundamental basis from complexity theory to address flow and transport in Earth media, and a wealth of related phenomena.The application of complexity to porous media is highly relevant for the flow of water through the random network we call soil, providing a direct relevance to the water transpired through the directed network that we call vegetation, as well as for interactions between the two (Hunt and Manzoni, 2015). Over the past 25 years it has been possible to generate an understanding of soil formation, vegetation growth and productivity, processes connected by their scaling relationships, the importance of water flow to each, and their links with the water balance and the highly permeable zone near Earth's surface, where life thrives (Hunt et al., 2021) - an interesting link between the critical phenomenon of percolation (Sahimi and Hunt, 2022) and the critical zone of research.

In short, it is possible to generate a nearly 1:1 correspondence between percolation concepts (as applied to networks), and familiar concepts, or even terms, in the ecohydrology/soil physics domains (Hunt, 2005). Hydraulic conductivity is generated through solutions of Kirchoff's laws on random resistor networks (equivalent to Laplace's equation on a heterogenous continuum), hysteresis is described through the distinction between percolation accessibility and Young-Laplace allowability (Heiba et al. 1983; Heiba et al. 1992; Hunt, 2004), the critical volume fraction for percolation is the residual water content, with relevance to the permanent wilting point of vegetation, invasion percolation is relevant to soil wetting (Wilkinson and Willemsen, 1983), the spatio-temporal scaling of conservative solute transport (e.g., Sahimi and Imdakm, 1988) can be used to generate the time and flux dependence of chemical weathering and other surface reactions in porous media, etc (Hunt et al. 2015). Although, in related scientific disciplines, such as chemical and petroleum engineering, a considerable body of work applying percolation theory to hysteresis, single and multi-phase flow, saturation, and transport exists (starting with Larson et al. 1977; 1981ab, Heiba et al. 1982; Sahimi and Imdakm, 1988; Heiba et al. 1992), apart from a relatively small number of papers that appeared in the late 1980's and early 1990's (e.g., Charlaix et al. 1987; Lenormand and Zarcone, 1989; Yortsos et al. 1993; Berkowitz and Balberg, 1993), Berkowitz and Ewing (1998), mainstream hydrology and soil physics have tended to neglect the subject. A mathematics dissertation on percolation in hydrology makes this point unintendedly [1]; the references it cites using percolation in hydrology are only five, including only Berkowitz and Ewing (1998) as a familiar reference, with the remaining either in the petroleum engineering or physics literature. This makes for a discussion of the history of application of percolation concepts in the realm of hydrology a peculiar affair, in which a wide range of topics has been addressed, but not by a wide range of authors - and many of the problems addressed were published first in petroleum engineering journals. As a consequence, Hunt (2004), for example, would have addressed hysteresis using the percolation concept of accessibility without reference to previous work (Heiba et al., 1983) if it weren't that one of the referees chosen for the paper was a petroleum engineer, as the soil physics and hydrology communities were largely, or completely, unaware of the connection. Nevertheless, Hunt (2004) did go further in identifying a critical volume fraction for percolation from knowledge of soil particle size data and the Soil Water Retention Curve to actually predict the imbibition curve without use of unknown parameters.

Institutional History of Hydrologic Sciences: AGU, NSF, CUAHSI, and Opportunities Delayed

As difficult as the assimilation of the fundamental evolution of percolation theory into hydrology has been, its struggles only parallel those associated with the assimilation of hydrology into geophysics. Even today, care is taken to distinguish hydrology from geophysics, of which the hydrologic sciences should be a key constituent, as they stitch virtually all its pieces together. Water is the foundation of life and its history on this planet, and together with oxygen - a product of photosynthesis - what distinguishes our planet and its atmosphere from its neighbors, Venus and Mars. In the critical zone, water connects biology and geochemistry and meets the rock cycle; the deep water cycle helps facilitate tectonics, and in the atmosphere, water transport is critical to the redistribution of solar energy.

As part of an eight-year effort to establish the Hydrology section of AGU, in Robert Horton's 1931 address of AGU's annual meeting (NAS, 1991), he defined the "science of hydrology," and ultimately the scope of the EAR Hydrologic Sciences Program thus, "More specifically, the [purpose of the] field of hydrology, treated as a pure science, is to trace out and account for the phenomena of the hydrologic cycle." The "business of hydrology" is then to solve the companion water balance equation (Dooge, 1987), which, in forms of varying detail, partitions the water arriving at the terrestrial Earth surface into its sundry pathways. A recently archived page [2] of the Hydrologic Sciences program of the USA National Science Foundation reinforces that emphasis on the water cycle, stating in its opening sentence that it "supports basic research on the fluxes of water in the terrestrial environment that constitute the water cycle". The simplest form of the water balance equation defines the principal fluxes of the water cycle. Some returns to the atmosphere through the process of evapotranspiration), some runs off in the streams, of which part remains on the surface and the rest penetrates the land surface. The term "percolation" is typically used for that part of the water that enters, and then travels downward through the soil. This term, though related in meaning to the subject of "percolation theory" or "percolation concepts," should not be confused with the branch of complexity that can address the generalized movement of fluids, solutes, charges, or heat through heterogeneous media. Nevertheless, it may be puzzling that such a careful distinction is required, since acceptance of the fundamental identity of soil percolation as a particular manifestation of a percolation process could perhaps help foster unity.

Understanding the Difficulty of "Technology Transfer"

Hunt and Sahimi (2017) referred to the proposed implementation of percolation concepts in the hydrologic sciences as a "Technology Transfer." Such transfer has largely not taken place. It is likely that the explanation for some of the unfamiliarity of percolation concepts within the hydrology community is traceable to the longer arc of scientific advances. Serious development of percolation theory and its relationship to phenomena involving movement of charges, fluid, or solutes wasn't initiated until after 1970 (mainly in the physics literature, e.g., Pollak 1972), while significant advances in the theory of solute transport in porous media were still being made in that venue until after 2010 (e.g., Ghanbarian et al. 2013). In view of the 1970's percolation technology transfer from physics to chemical engineering in the direction of hydrology, perhaps "Opportunities in the Hydrologic Sciences" (discussed further below) holds a clue (NAS, 1991, p. 87):"Early methods to deal with the transport of reactive solutes often were adopted from the chemical engineering literature. However, significant differences exist between solute transport processes taking place in fixed-bed chemical reactors and those occurring in sediments of aquifers or soils. Methods for describing solute transport in geologic media have had to outgrow their roots in chemical engineering and other nonhydrologic sciences."

Yet, it was precisely in chemical and petroleum engineering where the effects of heterogeneity and connectivity on flow and transport were being better understood using percolation theory. And, though probably not generally known in 1991, however, there was the problem of an up to six order of magnitude discrepancy between field and lab measurements of chemical weathering rates (White and Brantley, 2003), for which the associated time dependence, a decreasing power-law was not understood, though it is now recognized as related to the decay of solute transport velocities in time and space.

During this critical time period, 1975 - 1995, guidance for applying percolation in hydrology was scant and, to some extent, uninspiring. For example, the Berkowitz and Balberg (1993) review of percolation applications in hydrology focused on calculating the hydraulic conductivity with an algorithmic approach involving two parameters, a non-universal exponent, and a non-universal threshold, to describe a two-parameter function. However, this treatment is essentially indistinguishable from common phenomenological treatments in the soil physics literature, which consider either one, or the other, or both (the threshold and the power) as adjustable parameters. Moreover, the building blocks for calculating solute transport using the fractal dimensionality of the percolation backbone (Lee et al. 1999), and even the results for the value of this exponent (Sheppard et al. 1999), were only clarified at the end of the 1990's. Thus, it took nearly 30 years for percolation theory itself to develop to the extent that its fundamental structure could be readily adapted to the problems of solute transport in porous media. By that time a number of other currents in hydrology had taken hold. By the late 1980's, Mandelbrot's 1982 book, the Fractal Geometry of Nature, was motivating those who were seeking new vision to look for solutions to the problems facing subsurface hydrology in fractal models of both porous media and fracture networks. Perturbation theory had been adopted by leading theorists, where it became known as "Stochastic Subsurface Hydrology." At about the same time, following perhaps the example of physics, computational methods were becoming dominant in the physics of porous media, whose basis of study had long been the partial differential equations of conservation - of, e.g., mass and energy, as applied to the continuum model of the medium. But, as subsurface hydrology is only part of hydrology, this discussion is only part of the story.

Hydrology underwent explosive, but not consistent, development starting in the 1970's. Consider the following quote from Vit Klemes (1988), "'we have not one but many perspectives of hydrology’ as J.C.I. Dooge (1987) pointed out and, which is worse, that the one perspective missing is - - the hydrological perspective of hydrology." It may yet become clearer, which missing perspective is most damaging in its absence. Klemes also stated, "Commenting on hydrology as one of the geophysical sciences, Bras and Eagleson (1987) say ‘in the modern science establishment, this niche is vacant.’" Klemes' antidote was positive, yet pregnant, "due to a unique historical coincidence, we have entered a relatively short period which is extremely favourable for starting an effective treatment and that such an opportunity may not be repeated." What was happening at that time and is there any chance for, or need for, a repeat?

During the late 1980's, the program of hydrology was eliminated from the Engineering Directorate of the USA National Science Foundation and for a few years hydrology had no home at NSF at all. The community, with nearly all the best-known hydrologists of the time (including the above Dooge and Klemes, future Nobel laureate, Stockholm Water Prize Recipient, and NSF Director), put together the 1991 report, Opportunities in the Hydrologic Sciences (National Academy of Sciences, 1991) (also known as the Blue Book, or Eagleson Report) which was distributed through the National Research Council (NAS) as part of an effort to establish a Hydrologic Sciences Program in the Geosciences Directorate. The fundamental tenet of the Blue Book was:

"We cannot build the necessary scientific understanding of hydrology at a global scale from the traditional research and educational programs that have been designed to serve the pragmatic needs of the engineering community."

Notice the understanding that a revision of curriculum, infrastructure, and scale were all incorporated into a single sentence. That effort succeeded at about the same time, with L. Douglas James as the Hydrologic Sciences Program's first director (and a first year's budget of less than $1,000 K). The Blue Book had recognized the need to address non-linearities, scaling issues, and the water cycle, including its intimate connection with life. However, by the early 2000's it had become clear to the community that the scope of institutional support and the vision of the Eagleson Report were sufficiently incomplete as to require additional initiatives; a Water-Earth-Biota committee had published a manifesto in Eos [3], which helped lead the way to the formation of CUAHSI, and momentum had grown for the establishment of the Critical Zone research network, which was developed through NSF EAR around 2008 [4]. Despite the explicit understanding of the need to link scales all the way to the global, it can be seen today that the scales addressed in the Eagleson report were rather detached from those of the Critical Zone, as evident in this diagram relating percolation theoretical scaling (from Hunt et al. 2021) and the Stommel diagram from the Blue Book (Figure 2.9, p. 59)  .What is significant here is: 1) that the scaling relationships denoted by the blue, green, and brown lines all originate at the same pore scale in space and time) and 2) that the spatial scales of the Blue Book are horizontal, while the upper limit of vertical scales associated with the Critical Zone development (in magenta) are on the order of 100m, which lies almost entirely below the "local" scale. Nevertheless, the scaling relationships based at the pore scale link the largest horizontal scales (river drainages) with the vertical scale of the CZ as expressed in soil depth and tree height, and with the 10km horizontal scale of the CZ (clonal vegetation). The dashed lines represent the largest continental extent and the time since the break-up of Pangaea. To understand this better, consider that the green and grey entries represent vegetation growth, and the horizontal extent of such monogenetic plants exceeds the CZ depth only in clones, while the brown entries represent soil depth, which exceeds the usual CZ depth studied only on scales of about 150 million years or so. The scaling in this diagram is discussed further below.

.What is significant here is: 1) that the scaling relationships denoted by the blue, green, and brown lines all originate at the same pore scale in space and time) and 2) that the spatial scales of the Blue Book are horizontal, while the upper limit of vertical scales associated with the Critical Zone development (in magenta) are on the order of 100m, which lies almost entirely below the "local" scale. Nevertheless, the scaling relationships based at the pore scale link the largest horizontal scales (river drainages) with the vertical scale of the CZ as expressed in soil depth and tree height, and with the 10km horizontal scale of the CZ (clonal vegetation). The dashed lines represent the largest continental extent and the time since the break-up of Pangaea. To understand this better, consider that the green and grey entries represent vegetation growth, and the horizontal extent of such monogenetic plants exceeds the CZ depth only in clones, while the brown entries represent soil depth, which exceeds the usual CZ depth studied only on scales of about 150 million years or so. The scaling in this diagram is discussed further below.

Summary of Juxtaposed Histories

Despite its evident relevance in addressing problems of scale, heterogeneity, and connectivity, percolation remains, at the very least, an underutilized tool in hydrology and soil science. In particular, between the two of them, the reviews of these issues in hydrology, Kitanidis (2015) ("Persistent questions of heterogeneity, uncertainty, and scale in subsurface flow and transport") and soil physics, Jury et al. (2011) ("Kirkham's legacy and contemporary challenges in soil physics research"), mention the word percolation one time.

Universal scaling results from percolation theory, which quantifies the geometry and topology of paths of least resistance through the physical network representing the porous medium, unifies not only pore and continental scales, but research initiatives as disparate as the foundations of CUAHSI, the Hydrologic Science Program of the USA NSF, and the network of Critical Zone observatories. The theory itself thus has the potential to address some of the most serious conceptual and institutional barriers to the advancement of Hydrologic Science, an issue of such importance that Klemes (1987) after two short sections defining science and technology, addressed the main theme of his essay, "Hydrology: A Science or a Technology?" His answer was provided at the beginning: "In practice, hydrology is regarded mostly as a technological discipline rather than a science; this attitude is responsible for much bad science in hydrology which, in turn, has led to much bad technology in applied disciplines."

25 years ago, when I entered the field of subsurface hydrology as an independent scientist 15 years past my Ph.D. and with several retrainings behind me, it was clear to me only that one should not treat a primarily deterministic problem of flow and transport in heterogeneous media with stochastic methods. With hindsight, I can see that I have consistently followed Vit Klemes' advice in not promising what I did not know could be done, insisting only that it was important to get the basic science correct. Now, I can finally see that the tools I brought with me can be brought to bear even on the central problem of hydrology, solution of the water balance.

Percolation Advances in Hydrologic Science

Solute Transport

In spite of the relative disconnect between practitioners of hydrology and those of percolation, percolation's notable successes should be outlined here. These include the understanding of nearly 2000 measurements of the dispersivity, both of reactive and conservative solutes, over length scales of 10's of microns to ten kilometers, which are in good agreement with the predictions of percolation theory (Hunt et al. 2011), Figure 11 from [5]  .These results are in general accord with the theoretical framework of the continuous time random walk, or CTRW, (Hunt et al. 2011), but, in contrast to the CTRW, the exponents that determine the power-law decay in the arrival time distribution are known and specific to particular percolation situations, such as invasion (for imbibition or drying) or random (full saturation), and whether the network representation of the medium is effectively 2D or 3D. The results of this figure, moreover, help to resolve a discussion in the community as to what range of scales the approximately linear dependence of the dispersivity holds. The associated research into the (non-) scale-dependence of the hydraulic conductivity, but more importantly the result that the solute velocity is a diminishing function of scale, indicate that there is no relationship between an observed increase in mean hydraulic conductivity with scale and an observed increase in dispersivity. In an important follow-up, Ghanbarian et al. (2013) [6] showed in Fig. 12

.These results are in general accord with the theoretical framework of the continuous time random walk, or CTRW, (Hunt et al. 2011), but, in contrast to the CTRW, the exponents that determine the power-law decay in the arrival time distribution are known and specific to particular percolation situations, such as invasion (for imbibition or drying) or random (full saturation), and whether the network representation of the medium is effectively 2D or 3D. The results of this figure, moreover, help to resolve a discussion in the community as to what range of scales the approximately linear dependence of the dispersivity holds. The associated research into the (non-) scale-dependence of the hydraulic conductivity, but more importantly the result that the solute velocity is a diminishing function of scale, indicate that there is no relationship between an observed increase in mean hydraulic conductivity with scale and an observed increase in dispersivity. In an important follow-up, Ghanbarian et al. (2013) [6] showed in Fig. 12  the ability to predict the entire distribution of solute arrival times as a function of saturation for which all the parameters are determined with reference either to universal exponents from percolation theory, or specific system dependent properties obtained from fits to water retention curves. Such prediction of non-Gaussian dispersion has not been accomplished in other theoretical frameworks.

the ability to predict the entire distribution of solute arrival times as a function of saturation for which all the parameters are determined with reference either to universal exponents from percolation theory, or specific system dependent properties obtained from fits to water retention curves. Such prediction of non-Gaussian dispersion has not been accomplished in other theoretical frameworks.

Chemical Weathering and Soil Formation

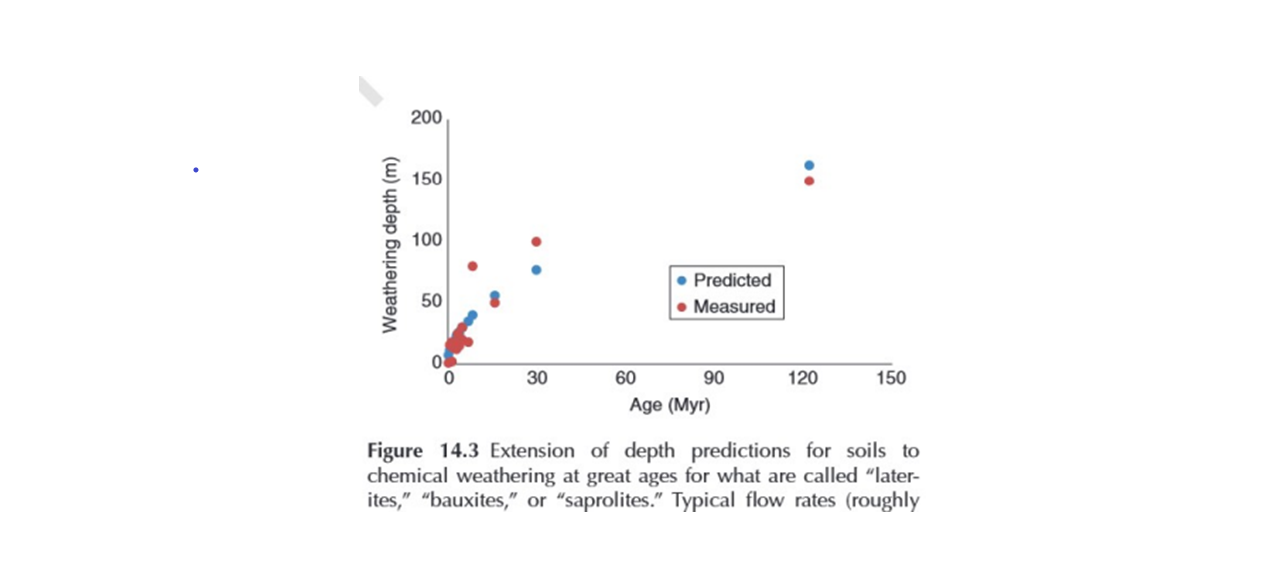

The ability to predict non-Gaussian dispersion has led to successful predictions of chemical weathering [7]and soil formation. By equating, in the absence of erosion, the solute transport distance and the soil (or chemically weathered depth), one can generate a concrete example of Jenny's "clorpt" soil forming factors equation (with depth proportional to the time to the 1/1.87 power and 1.87 the fractal dimension of the percolation backbone). In addition to the exponent, the equation relating the time of transport to the Euclidean distance of transport requires two parameters from consistency of units: a length scale equal to a median particle size, and a time scale, equal to the mean time it takes water to flow that distance. Why this solves Janny's equation is as follows: the form of the equation and the flow rate depend on climate variables and vegetation, the particle size reflects the parent material, time is explicit, and the relief enters below, when erosion rates are addressed. The simple scaling realtionship predicts deep chemical weathering depths over time scales of 1 million to 135 million years in a figure from Hunt et al. (2021a)  .This result is obtained by substituting into the clorpt equation a typical vadose zone annual vertical flow rate proportional to P-ET of about a half meter per year and a typical particle size in the mid silt range. If erosion is relevant, the time derivative of the analogue to Jenny's equation generates the soil production function and forcing the equality of soil production and soil erosion for steady-state leads to a second simple equation, which describes soil depths as a function of relief through the erosion rate, which has been tested over a range of slope angles

.This result is obtained by substituting into the clorpt equation a typical vadose zone annual vertical flow rate proportional to P-ET of about a half meter per year and a typical particle size in the mid silt range. If erosion is relevant, the time derivative of the analogue to Jenny's equation generates the soil production function and forcing the equality of soil production and soil erosion for steady-state leads to a second simple equation, which describes soil depths as a function of relief through the erosion rate, which has been tested over a range of slope angles  and found accurate enough to be able to distinguish which slopes are susceptible to landslides (Yu et al., 2019). In this version, the soil depth is proportional to P-ET to the 1.15 power, where 1.15 is 1/(Db-1), and Db is the fractal dimensionality of the percolation backbone. Or, if neither simple formula is sufficient, the resulting equation for soil depth can be solved numerically, as in Egli et al. (2018) with predictions shown in the Figure

and found accurate enough to be able to distinguish which slopes are susceptible to landslides (Yu et al., 2019). In this version, the soil depth is proportional to P-ET to the 1.15 power, where 1.15 is 1/(Db-1), and Db is the fractal dimensionality of the percolation backbone. Or, if neither simple formula is sufficient, the resulting equation for soil depth can be solved numerically, as in Egli et al. (2018) with predictions shown in the Figure  .What is most important about this comparison is that the particle sizes, the erosion rates, and the infiltration rates were all determined by neutral protocols for extraction from databases developed by Markus Egli, who was responsible for generating the age and depth results of most of the soils as well. This means that zero adjustible parameters were employed through the entire database.

.What is most important about this comparison is that the particle sizes, the erosion rates, and the infiltration rates were all determined by neutral protocols for extraction from databases developed by Markus Egli, who was responsible for generating the age and depth results of most of the soils as well. This means that zero adjustible parameters were employed through the entire database.

Vegetation Growth and Productivity

Predictions of vegetation growth and net primary productivity are documented in the ecology literature (Hunt et al. 2020; 2022) [8] [9], in soil sciences (Hunt, 2017)[10], and in greater detail in the book, Networks on Networks: The Physics of Geobiology and Geochemistry (Hunt and Manzoni, 2015). The scaling function for root radial extent, equivalent to height for length scales ca. 1m to 40m (Fig. 6.6 from Hunt and Manzoni, 2015), is analogous to the result for Jenny's clorpt equation, but with the 2D optimal paths exponent relating time and length scales. The 2D optimal paths exponent is smaller, 1.21, yielding an effective tortuosity which is much smaller, and a growth rate which is much higher. The proposed scaling of vegetation growth is shown in Hunt and Manzoni (2015) to reduce the predicted allometric scaling exponent relating tree height to diameter from 2/3 to (2/3)/1.21 = 0.55, which is found to match accurately the observed allometric scaling of tree height vs. diameter by comparison of the results with NSF sponsored metastudies involving approximately 100,000 individual observations [11] [12]. The role of the infiltration flux in soil formation is played in vegetation growth by the transpiration [13]. In that reference it is shown that the variability of tree height and growth rates in space is also accounted for by the transpiration dependence, including examples of slope aspect and curvature, climate, substrate conditions (rock crevices or soil, compaction, and hydrophobicity) and xylem hydraulic conductivity. In [14] it was shown that the proposed relationship is so accurate that it can predict tree heights from cumlulative transpiration with a less than 1% discrepancy at 11 years (15m) and only 2-3 % discrepancy at an age of 200 years (>80m). As shown in the thumbnail unpublished figure , data from Figure 3d of CLark and Clark (2001) [15] is in perfect agreement with the prediction of the growth rate using a first year transpiration of 2m. Note that the red line is the prediction, the grey line a prediction of a linear growth rate. This particular result augments the published data that are summarized in the next figure from Hunt et al. (2021b)

(Fig. 6.6 from Hunt and Manzoni, 2015), is analogous to the result for Jenny's clorpt equation, but with the 2D optimal paths exponent relating time and length scales. The 2D optimal paths exponent is smaller, 1.21, yielding an effective tortuosity which is much smaller, and a growth rate which is much higher. The proposed scaling of vegetation growth is shown in Hunt and Manzoni (2015) to reduce the predicted allometric scaling exponent relating tree height to diameter from 2/3 to (2/3)/1.21 = 0.55, which is found to match accurately the observed allometric scaling of tree height vs. diameter by comparison of the results with NSF sponsored metastudies involving approximately 100,000 individual observations [11] [12]. The role of the infiltration flux in soil formation is played in vegetation growth by the transpiration [13]. In that reference it is shown that the variability of tree height and growth rates in space is also accounted for by the transpiration dependence, including examples of slope aspect and curvature, climate, substrate conditions (rock crevices or soil, compaction, and hydrophobicity) and xylem hydraulic conductivity. In [14] it was shown that the proposed relationship is so accurate that it can predict tree heights from cumlulative transpiration with a less than 1% discrepancy at 11 years (15m) and only 2-3 % discrepancy at an age of 200 years (>80m). As shown in the thumbnail unpublished figure , data from Figure 3d of CLark and Clark (2001) [15] is in perfect agreement with the prediction of the growth rate using a first year transpiration of 2m. Note that the red line is the prediction, the grey line a prediction of a linear growth rate. This particular result augments the published data that are summarized in the next figure from Hunt et al. (2021b)  . It should be noted that upscaling the non-linear scaling relationship for vegetation growth to yearly time scales upscales (Hunt et al. 2017) the pore-scale flow rate of 25m per year to a transpiration rate of about 2m per year. In this figure, it is notable that the same pore-scale flow rate, equal to a maximum precipitation of about 10m per year divided by a typical soil porosity, limits crop growth (linear in time), natural vegetation growth, and soil formation, confirming the relevance of advective, rather than diffusive, processes to all three. In view of the confirmation that plant roots mostly followed paths with tortuosity commensurate with the 2D optimal paths exponent of percolation thoery, Hunt (2017) proposed that the root fractal dimensionality should be equal to the 2D mass fractal dimensionality of percolation theory, equal to 1.9, though some examples with that dimensionality equal to the 3D value of 2.5 could also be expected to be sometimes relevant, particularly where root systems were deeper (in water-limited ecosystems). As a consequence, it was proposed that the net primary productivity - plant matter produced in one year, should be proportional to the 1.9 power. This result, confirmed by comparing with 20 existing studies on NPP in [16] was similar to the empirical one (with exponent 1.6) proposed by Rosenzweig (1968) (which was included in the metastudy cited).

. It should be noted that upscaling the non-linear scaling relationship for vegetation growth to yearly time scales upscales (Hunt et al. 2017) the pore-scale flow rate of 25m per year to a transpiration rate of about 2m per year. In this figure, it is notable that the same pore-scale flow rate, equal to a maximum precipitation of about 10m per year divided by a typical soil porosity, limits crop growth (linear in time), natural vegetation growth, and soil formation, confirming the relevance of advective, rather than diffusive, processes to all three. In view of the confirmation that plant roots mostly followed paths with tortuosity commensurate with the 2D optimal paths exponent of percolation thoery, Hunt (2017) proposed that the root fractal dimensionality should be equal to the 2D mass fractal dimensionality of percolation theory, equal to 1.9, though some examples with that dimensionality equal to the 3D value of 2.5 could also be expected to be sometimes relevant, particularly where root systems were deeper (in water-limited ecosystems). As a consequence, it was proposed that the net primary productivity - plant matter produced in one year, should be proportional to the 1.9 power. This result, confirmed by comparing with 20 existing studies on NPP in [16] was similar to the empirical one (with exponent 1.6) proposed by Rosenzweig (1968) (which was included in the metastudy cited).

Water Balance and Net Primary Productivity

The above scaling results for vegetation growth and soil formation have been combined with a hypothesis regarding ecosystem productivity to generate a theory of the water balance [[17], published in WRR. The hypothesis that formed the basis of this theory is that the ecosystem that exists is the one that is most successful at converting atmospheric carbon dioxide to biomass. Since plant roots occupy the top layer of the soil, the biomass sequestered by plants and their symbionts is not given simply by the result above for NPP; that result must be multiplied by the soil depth. But, in steady-state, the soil depth is proportional to the precipitation less evapotranspiration to a power near 1 (=1.15, see above). Such a product can be optimized by differentiating and setting equal to zero, yielding ET = 0.623 P, where the factor 0.623 = 1.9/(1.15 + 1.9) is a combination of universal exponents from percolation theory. Thus, vegetation cannot grow without soil, so some of the water must go to soil formation, but most of the water must go to the plants (see the UT Dallas news video produced to summarize this research at https://youtu.be/xv-n54NTd9M, which was distributed to AGU, GSA, and the AAAS). This result, which is almost identical to the global result (0.634 P), was extended to energy-limited systems by applying the optimization only to the fraction of the precipitation which equals the potential evapotranspiration, PET (letting the remaining P run off) and for water-limited ecosystems only to the vegetated ground, (letting the remaining P evaporate). It is important that this conceptual understanding leads to a continuous functional form for the water balance, but not for its derivative, which shows up in streamflow elasticity below.

In putting together this history, it has become clear to me that, unbeknownst to us, we had followed a blueprint set down in the Blue Book on page 65-66 (with our own specific details in bold):

"In plant dynamics it is known that the abundance of species and their spatial distribution are related to environmental conditions called ecological optima. A natural speculation is that these conditions are the preferred operating domain of the climate-soil-vegetation system. The key question relates to what the optimality criteria are that direct the functioning of this system. Where water is the driving force of the system, a logical hypothesis is that the optimality criteria are related to the key hydrologic variables [fluxes]. Among the exciting scientific challenges are the search for the optimality criteria [biomass production] under different types of constraints [water-limited and energy-limited] and the mathematical representation [setting the derivative with respect to evapotranspiration equal to zero] of these criteria. The fluxes of the key biological variables (e.g., biomass) are also intertwined with the operating chemical processes (e.g., carbon assimilation), which in turn are linked to hydrologic processes (e.g., evapotranspiration). From such relationships it is clear that hydrology is a fundamental structural component of the biogeochemical cycles."

Compare the blue book with our abstract (Hunt et al. 2021):

"The ecosystem net primary productivity is expressed in terms of soil formation and vegetation growth, which is mathematically optimized with respect to the water partitioning, generating directly the value ET/P. The mathematical optimization is based on the general ecological principle that dominant ecosystems tend to be those that, for any given conditions, maximize conversion of atmospheric carbon to biomass. It is shown that application of the results of mathematical optimization to water-limited ecosystems is possible by applying the optimization only to a vegetation covered portion of the surface. For energy-limited ecosystems,the optimization can be applied only to a portion of the precipitation equal to PET, assuming that the remaining P simply runs off," and, from the body, "But, for the 2D case, Equation 6 only accounts for the horizontal component of the root development affecting the NPP, and must also be multiplied by the vertical extent, d. Thus, root mass may be mostly confined to 2D, but will still be proportional to the depth of the root mass, which is very nearly the solum depth." Now, Nijzink and Schymanski's (2022) statements clarify the one-to-one correspondence between our two works:

"So far, the Budyko framework was related to optimality theory only a few times, mostly by applying thermodynamic optimality principles and constraints in numerical experiments (Porada et al., 2011; Kleidon et al., 2014; Westhoff et al., 2016; Wang et al., 2015). To our knowledge, the results presented here illustrate for the first time that an ecologically motivated optimality principle (maximum net carbon profit) leads to a close reproduction of the Budyko curve. Previously, Milly (1994) suggested that convergence towards the Budyko curve may be a result of plants optimizing their rooting depths to maximize transpiration in a given environment. However, here we found that convergence on the Budyko curve is likely the result of rooting depths, vegetation cover, and water-use strategies playing together in a way to satisfy a biological optimality principle."

Nijzink and Schymanski (2022) also point out that their results correspond closely to the best-fit parametric equation (Choudhury form, n = 1.49) for the FLUXNET data for the water balance reported by Williams et al. (2012). We have noted the same in a preprint submitted to STOTEN as shown in this figure adapted from Williams et al. (2012).

The central figure of Hunt et al. (2021a) includes the specific predictions of the water balance equation for the theoretical limits of root fractal dimension 1 and 3, the expected values from 2D and 3D percolation structures, 1.9 and 2.5, and the largest known example of a group of Great Plains grass species, 2.78  . The data, with which the comparison is made, are from the MOPEX experiment, processed by Gentine et al. (2012). The limits on the prediction are physically set, not by mathematics, chosen to correspond to particular regions of the Budyko space. The most likely range of data predicted is set by the 2D and 3D predictions. The shapes of the curves are actually better suited as data bounds than the usual predictions. One potential drawback was cited in this paper; the lack of continuity of the derivative of the water balance equation at aridity index 1, derived from the distinct physical limits applied for energy-limited and water-limited systems. However, the next comparisons demonstrate that such a sharp change in behavior is particularly well-suited to describing streamflow elasticity below.

. The data, with which the comparison is made, are from the MOPEX experiment, processed by Gentine et al. (2012). The limits on the prediction are physically set, not by mathematics, chosen to correspond to particular regions of the Budyko space. The most likely range of data predicted is set by the 2D and 3D predictions. The shapes of the curves are actually better suited as data bounds than the usual predictions. One potential drawback was cited in this paper; the lack of continuity of the derivative of the water balance equation at aridity index 1, derived from the distinct physical limits applied for energy-limited and water-limited systems. However, the next comparisons demonstrate that such a sharp change in behavior is particularly well-suited to describing streamflow elasticity below.

Our published theory of the water balance has made it possible to predict streamflow elasticity as a function of aridity index, both its median value and the distribution of values, as well as the net primary productivity as a function simultaneously of aridity index and solar irradiation. The latter is a simple plug-in of the water balance into the 2D result for NPP as a function of ET, and the former is generated by taking the logarithmic derivative of the streamflow Q with respect to the precipitation, P for the 2D result for ET. These results are still in review, but the primary comparisons with data are shown here.

. In the former image, the streamflow elasticity is first calculated assuming the traditional water balance equation with no storage changes, which give a median elasticity value. Repeating the calculations including changes in storage amounting to +10% of the precipitation or -30% of the precipitation bounds the range of predicted elasticity values. Note that the predicted double peak in elasticity values shows up in all the major data sets. In the latter image, we see that the same cross-over in functional form, which predicts a discontinuous derivative in the elasticity, produces a saturation of the NPP at low aridity index. We also compare our prediction of streamflow elasticity as a function of run-off ratio, both calculated allowing only variable storage change (values given on the figure), and capped at a maximum aridity index of 6, with data of Chiew et al. (2006)

. In the former image, the streamflow elasticity is first calculated assuming the traditional water balance equation with no storage changes, which give a median elasticity value. Repeating the calculations including changes in storage amounting to +10% of the precipitation or -30% of the precipitation bounds the range of predicted elasticity values. Note that the predicted double peak in elasticity values shows up in all the major data sets. In the latter image, we see that the same cross-over in functional form, which predicts a discontinuous derivative in the elasticity, produces a saturation of the NPP at low aridity index. We also compare our prediction of streamflow elasticity as a function of run-off ratio, both calculated allowing only variable storage change (values given on the figure), and capped at a maximum aridity index of 6, with data of Chiew et al. (2006)  .

.

For further confirmation, let's consider the implications for the water balance itself. We will compare the 2D prediction plus or minus the identical storage changes (+10% and -30%) that led to such a good accounting of the streamflow elasticity of Sankarasubramanian et al. (2006) across the USA with the MOPEX data for the annual water balance as presented by Gentine et al. (2012) in the figure  . Given that the identical theoretical description with the identical parameters accounts for the water balance, streamflow elasticity as a function of aridity (or humidity) index, and the net primary productivity simultaneously, I feel confident in saying that we have solved the fundamental problem of hydrology - at least as parsimoniously as will ever be done. Note that, in this latter figure, we have also shown the close correspondence to the upper bound of the optimal vegetation response (maximum carbon profit) as found by Nijzink and Schymanski (2022). Our purely theoretical optimum corresponds to the upper limit of their modeled optimal curves - it seems, the optimum of the optimal.

. Given that the identical theoretical description with the identical parameters accounts for the water balance, streamflow elasticity as a function of aridity (or humidity) index, and the net primary productivity simultaneously, I feel confident in saying that we have solved the fundamental problem of hydrology - at least as parsimoniously as will ever be done. Note that, in this latter figure, we have also shown the close correspondence to the upper bound of the optimal vegetation response (maximum carbon profit) as found by Nijzink and Schymanski (2022). Our purely theoretical optimum corresponds to the upper limit of their modeled optimal curves - it seems, the optimum of the optimal.

Summary, Including Relevance to Hydrologic Sciences, Present and Future

Water fluxes are central to soil formation and vegetation growth. The water balance is solved (Hunt et al., 2021) using an important ecological hypothesis. Subsequent work of Nijzink and Schymanski (2022) solves the same problem in the same way, verifying the mechanism, the details, and the results of our paper (though without citation). Requoting Dooge (1987), "The business of hydrology is solving the water balance." [18]. As pointed out above, NSF's Hydrologic Sciences Program has recognized the central position of the water balance in hydrology [19]. The Ecosystems Studies Program [20] tacitly elevates the water balance equivalently by stating its dedication "to advance understanding of: 1) material and energy fluxes and transformations within and among ecosystems.” Without the ability to quantify the energy made available through NPP, it will be difficult to quantify the secondary fluxes. Under Critical Zone research [21], we find, “The Critical Zone (CZ), from the top of the vegetation canopy to the base of the weathered bedrock, is where fresh water flows, soils are formed, and most terrestrial life flourishes on Earth.” With the cited research here, percolation theory has united these subjects into a coherent whole. By including the research that is still in review, the relevance for the future of hydrology is also made clear, given its current engagement with ungaged basins and with how climate change will affect dwindling water resources. Considering that the scaling relationships discussed unite such immense space and time scales, including subjects that have been considered as necessary to address through distinct research initiatives over a span of almost 20 years of infrastructure development, it becomes clear that its unifying potential is social as well as scientific. It is important that the unification of scales occurs because heterogeneities exist on all scales and that the paths of least resistance through them appear to be described using the particular set of fractal exponents that arise in universal applications of percolation theory.

Driese et al. (2021), in their 80-page Earth-history of evolution, soil formation, and atmospheric chemistry [22], advocated for the establishment of deep time Critical Zone observatories to complement the ones in existence. Hunt et al. 2021, in their summary chapter argued for a paradigm shift regarding soils and soil formation, noting that, among other apparent contradictions, the exponential soil production function commonly applied from geomorphology is incompatible with the power-law results for chemical weathering, as long as chemical weathering is indeed the principal limiting factor in soil formation. As the Earth's surface preserves a record of the past, it is clearly far from equilibrium. But that does not preclude the relevance of investigations based on complexity, including the statistical mechanics of percolation theory.

Conclusion

Whether Vit Klemes' implied question regarding the future of hydrologic sciences requires a reset seems pretty clear from the perspective of percolation; the answer is yes. Whether such an opportunity will return is no clearer from the percolation viewpoint than any other.

References

Berkowitz, B. and Balberg, I.: 1993, ‘Percolation theory and its application to groundwater hydrology’, Water Resources Research 29, 775-794.

Berkowitz, B., & Ewing, R. P. (1998). Percolation theory and network modeling applications in soil physics. Surveys in Geophysics, 19, 23-72. Bras, R. and Eagleson, P. S. 1987. Hydrology, the forgotten earth science, Eos 68 p. 227.

Broadbent, Simon R., and John M. Hammersley. "Percolation processes: I. Crystals and mazes." Mathematical proceedings of the Cambridge philosophical society. Vol. 53. No. 3. Cambridge University Press, 1957.

Charlaix, E., Guyon, E., and Roux, S. (1987). Permeability of a Random Array of Fractures of Widely Varying Apartures. Transport in porous media,2:31–43.

Chiew, F.H.S., Peel, M.C., McMahon, T.A., & Siriwardena, L.W. (2006). Precipitation elastic�ity of streamflow in catchments across the world. In, S. Demuth, A. Gustard, E. Planos, F. Scatena, & E. Servat (Eds.), Climate Variability and Change-Hydrological Impacts, IAHS, pp. 256-262.

Clark, D. A., & Clark, D. B. (2001). Getting to the canopy: tree height growth in a neotropical rain forest. Ecology, 82(5), 1460-1472.

Dooge JCI, 1987. Hydrology in perspective. Presented at Int. Symp. Water Future, IAHS and IAHR, Rome

Egli,M., A. G. Hunt, D. Dahms, G. Raab, C. Derungs, S. Raimondi, F Yu, 2018, Prediction of soil formation as a function of age using the percolation theory approach, Frontiers in Environmental Sciences, 28: https://doi.org/10.3389/fenvs.2018.00108

Friedman, S. P., and Seaton N. A, 1998. Critical path analysis of the relationship between permeability and electrical conductivity of three-dimensional pore networks, 34: Water Resources Research, 1703-1710

Gentine, P., D'Odorico, P., Lintner, B. R., Sivandran, G., & Salvucci, G. (2012). Interdependence of climate, soil, and vegetation as constrained by the Budyko curve. Geophysical Research Letters, 39(19).

Ghanbarian, B., Torres-Verdín, C., Skaggs,T. H. 2016. Quantifying tight-gas sandstone permeability via critical path analysis, Advances in Water Resources, 92, 316-322.

Ghanbarian, B., 2020. Applications of critical path analysis to uniform grain packings with narrow conductance distributions: I. Single-phase permeability, Advances in Water Resources, 137 103529.

Heiba, A. A., Sahimi, M., Scriven, L. E., and Davis, H. T. 1982. Percolation Theory of Two-Phase Relative Permeability, Society of Petroleum Engineers Paper 11015, 1-17.

Heiba, A.A., Davis, H.T., and Scriven, L.E. 1983. "Effect of Wettability on Two-Phase Relative Permeabilities and Capillary Pressures," paper SPE 12172 presented at the 1983 SPE Annual Technical Conference and Exhibition, San Francisco, Oct. 5-8.

Heiba et al., A. A., Sahimi, M., Scriven, L. E., and Davis, H. T., 1992. Percolation Theory of Two-Phase Relative Permeability, SPE Res Eng 7 (01): 123–132. Paper Number: SPE-11015-PA

Hunt, A. G., 2001, Applications of percolation theory to porous media with distributed local conductances, Advances in Water Resources, 24: 279-307.

Hunt, A. G., 2004. Continuum percolation theory for water retention and hydraulic conductivity of fractal soils: 2. Extension to non-equilibrium, Advances in Water Resources, 27, 245-257.

Hunt, A. G., 2005. Percolation theory and the future of hydrogeology, Hydrogeology Journal volume 13, pages 202–205.

Hunt, A. G., 2022. What perspective will best lead hydrology into the future? J. Jpn. Soc. Soil Phys. 152: 3-6.

Hunt, A. G., and , S., 2015. Networks on Networks: The Physics of Geobiology and Geochemistry, Morgan & Claypool (for the Institute of Physics), Bristol, United Kingdom.

Hunt, A. G., Ghanbarian, B., Skinner, T. E., and Ewing, R. P. 2015. Scaling of geochemical reaction rates via advective solute transport. Chaos 25, 075403 (2015); https://doi.org/10.1063/1.4913257

Hunt, A. G., B. Ghanbarian and R. Holtzman, 2017, Upscaling soil infiltration and evapotranspiration from percolation theory, Water 9: 104

Hunt, A. G., and Sahimi, M. 2017, Flow, transport, and reaction in porous media: Percolation scaling, critical path analysis and effective-medium approximation, Rev. Geoph. doi: 10.1002/2017RG000558.

Hunt, A. G., B. A. Faybishenko, and T. L. Powell, 2020, A new phenomenological model to describe root-soil interactions based on percolation theory, Ecological Modelling 433: 109205.

Hunt, A. G., B. A. Faybishenko, and B. Ghanbarian, 2021b, Predicting characteristics of the water cycle from scaling relationships, Water Resources Research, 57, e2021WR030808. https://doi.org/10.1029/2021WR030808

Hunt, A. G., Egli, M., and Faybishenko, B., 2021a. Hydrogeology, Chemical Weathering, and Soil Formation, AGU/Wiley, Geophysical Monograph Series.

Hunt, A.G., Faybishenko, B. and Powell, T.L., 2022. Test of model of equivalence of tree height growth and transpiration rates in percolation-based phenomenology for root soil interaction, Ecological Modelling.vol. 465(C), DOI: 10.1016/j.ecolmodel.2021.109853.

Jury, W. A., Or, D., Pachepsky, Y., Vereecken, H., Hopmans, J. W., Ahuja, L. R., Clothier, B. E., Bristow, K. L., Kluitenberg, G. J., Moldrup, P., Simunek, J., van Genuchten, M. Th., and Horton, R., 2011. Kirkham's legacy and contemporary challenges in soil physics research. Soil Science Society of America Journal, 75(5), 1589-1601.

Kitanidis, P. K., 2015. Persistent questions of heterogeneity, uncertainty, and scale in subsurface flow and transport. Water Resources Research, 51(8), 5888-5904.

Klemes, V., 1988. A hydrological perspective, J. Hydrol. 100 (1-3): 3-28.

Larson, R.O., Scriven, L.E., and Davis, H.T. 1977. Percolation Theory of Residual Phases in Porous Media, Nature, 268, 409-13.

Larson, R.O., Scriven, L.E., and Davis, H.T. 1981. Percolation Theory of Two-Phase Flow in Porous Media, Chern. Eng. Sci. 36, 57-73

Larson, R.O., Davis, H.T., and Scriven, L.E. 1981 Displacement of Residual Nonwetting Fluid From Porous Media, Chem. Eng. Sci. 36, 75-85.

Lee, Y., Andrade, J. S., Buldyrev, S. V., Dokholoyan, N. V., Havlin, S., King, P. R., Paul, G., and Stanley, H. E., 1999. Traveling time and traveling length in critical percolation clusters. Phys. Rev. E 60, 3425–3428.

Lenormand, R., & Zarcone, C. 1989. Capillary fingering: percolation and fractal dimension. Transport in porous media, 4(6), 599-612.

National Academy of Sciences, 1991, Opportunities in the Hydrologic Sciences, https://nap.nationalacademies.org/download/1543

National Research Council 1996. Rock fractures and fluid flow. Washington, DC: National Academy Press.

Nijzink, R. C., & Schymanski, S. J. (2022). Vegetation optimality explains the convergence of catchments on the Budyko curve. Hydrology and Earth System Sciences, 26(24), 6289-6309.

Pollak, M., 1972. A percolation treatment of dc hopping conduction, J. Non Cryst. Solids 11, 1–24. https://doi.org/10.1016.

Rosenzweig, Michael L. 1968. Net primary productivity of terrestrial communities: prediction from climatological data. The American Naturalist 102.923: 67-74.

Sahimi M, Imdakm O. A., 1988. The effect of morphological disorder on hydrodynamic dispersion in flow through porous media. J Phys A 21: 3833–3870

Sahimi, M., 1991. Flow phenomena in rocks: from continuum models to fractals, percolation, cellular automata, and simulated annealing, Reviews of Modern Physics 65 (4), 1393.

Sahimi, M., 2022. Applications of Percolation Theory, 2nd edition. Taylor & Francis, London.

Sahimi, M., and Hunt, A. G., 2022. Complex Media and Percolation, a Volume in the Springer Encyclopedia of Complexity and Systems Science Series, Robert Meyers, Editor-in-Chief, Springer Nature, N.Y.

Sankarasubramanian, A., Vogel, R.M., & Limbrunner, J.F. (2006). Climate elasticity of streamflow in the United States. Water Resources Research, 37(6), 1771-1781. https://doi.org/10.1029/2000wr900330

Sheppard, A. P., Knackstedt, M. A., Pinczewski, W. V., and Sahimi, M., 1999. Invasion percolation: New algorithms and universality classes, J. Phys. A: Math. Gen. 32, L521–L529.

Yortsos, Y. C., Satik, C., Bacri, J. C., & Salin, D. 1993. Large-scale percolation theory of drainage. Transport in Porous Media, 10, 171-195.

White, A. F., and S. L. Brantley (2003), The effect of time on the weathering rates of silicate minerals. Why do weathering rates differ in the lab and in the field?, Chem. Geol.,202, 479–506.

Wilkinson, D., & Willemsen, J. F. (1983). Invasion percolation: a new form of percolation theory. Journal of physics A: Mathematical and general, 16(14), 3365.

Williams, C.A.; Reichstein, M.; Buchmann, N.; Baldocchi, D.; Beer, C.; Schwalm, C.; Wohlfahrt, G.; Hasler, N.; Bernhofer, C.; Foken, T.; et al. Climate and vegetation controls on the surface water balance: Synthesis of evapotranspiration measured across a global network of flux towers. Water Resour. Res. 2012, 48, W06523, doi:10.1029/2011WR011586.

Yu, F., A. G. Hunt, M. Egli, and G. Raab, 2019, Comparison and contrast in soil depth evolution for steady-state and stochastic erosion processes: Possible implications for landslide prediction, Geochemistry, Geophysics, Geosystems, https://doi.org/10.1029/2018GC008125